Eliza Hart’s latest project explores the concept of football acting as a religion within English culture.

In primary school, I vividly remember standing in a perfectly formed line with my classmates, enthusiastically singing "We've got the whole world in our hands." It was a moment of sheer joy, uninhibited by any teenage angst or adult questioning.

Fast forward to secondary school. We began to explore our identities and cringed at the thought of singing songs in front of our classmates. Our teacher would stand on the sidelines, casting disapproving glances as we barely moved our lips, attempting to sing as softly as humanly possible. The days of carefree singing seemed long gone, overshadowed by self-consciousness and the desire to fit in.

My introduction, like most, of going to football games was with an adult, or a little later, with friends. Reminiscent of school days, we stand in a line fervently chanting the name of our favourite player, elevating them to a god-like status. It’s a nostalgic nod to a time we thought was lost when we put down our pens after final exams. But there we were, caught up in the moment, reliving the pure, unadulterated joy of singing as one, and not a care in the world. So what changed?

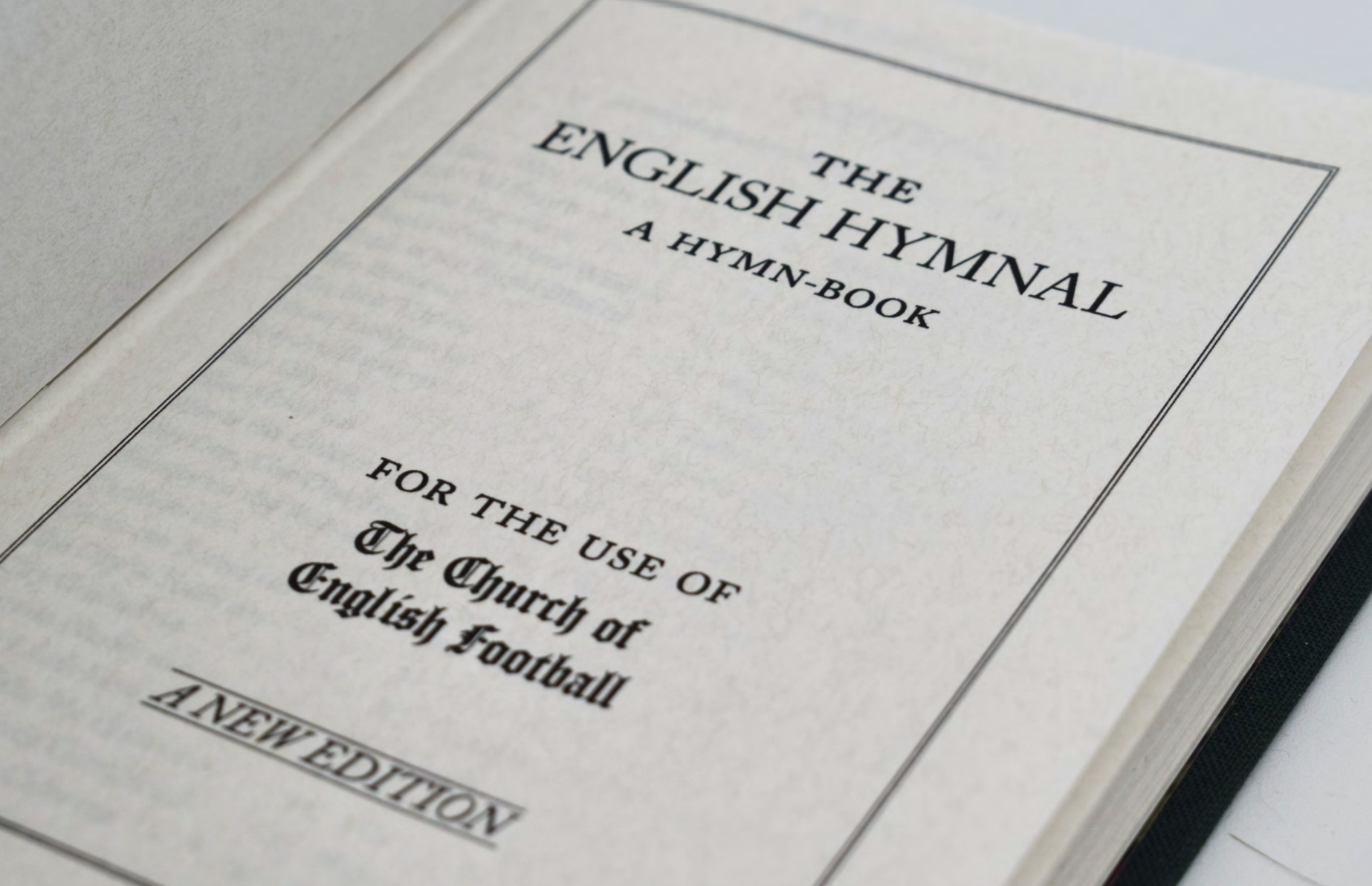

Over the past year, artist Eliza Hart has been creating a series exploring this very concept of football masquerading as a religion within English culture. In an era where traditional religious practices have waned, her project suggests that football has emerged as a spiritual force, captivating fans with an intensity and devotion reminiscent of the religious fervour of days gone by.

Captivated by the parallels drawn between singing about the god that exists within religion and the “god” who is your top goal scorer of the season, we sat down with Eliza and discussed the concept of singing at football games.

I find it facsinating that one day people started singing at games and that stuck ever since. Why did that happen and why did you think it naturally evolved?

The tradition of chanting and singing at football matches emerged as a way for fans to express their support for their team, and react the action taking place on the pitch and amongst the stalls. I think rivalries between football clubs have played a big role in the development of chants. Supporters would create chants to taunt their rivals. Rivalries definitely fuelled the creativity and competitiveness of the chants, as fans sought to outdo each other in terms of provocativeness and volume. Football chants have been sung by fans since the late 19th century, but chants became integral aspect of football fan culture in the 1960s, shifting from adaptions of Victorian hall songs to adaptions of pop songs, as well more taunting/self-depracating call and responses, which then escalated throughout the 70s and 80s. The 1962 World Cup was also pretty significant in influencing different chanting styles on an international scale, for example, Liverpool borrowed the beats of “Brazil, cha-cha-cha” to create “Liverpool, clap-clap-clap.”

Both football and religion can be problematic in their own rights, what you think football could learn from religion and religion from football?

I think football culture in England has made pretty significant strides in becoming more inclusive to different groups of people, with increased representation, most notably within women’s football, after all the recent success of the Lionesses. While English football has made progress in becoming more accessible and inclusive to marginalised groups, there are still significant barriers that need to be removed. However, in answer to this question, it is worth noting that some religious practices tend to be more exclusive, so perhaps it’s possible for religion to draw lessons from the inclusivity demonstrated by football.

As players move around from club to club, new songs are created and retired. During the research for this project, did you find out if clubs record songs from past and present?

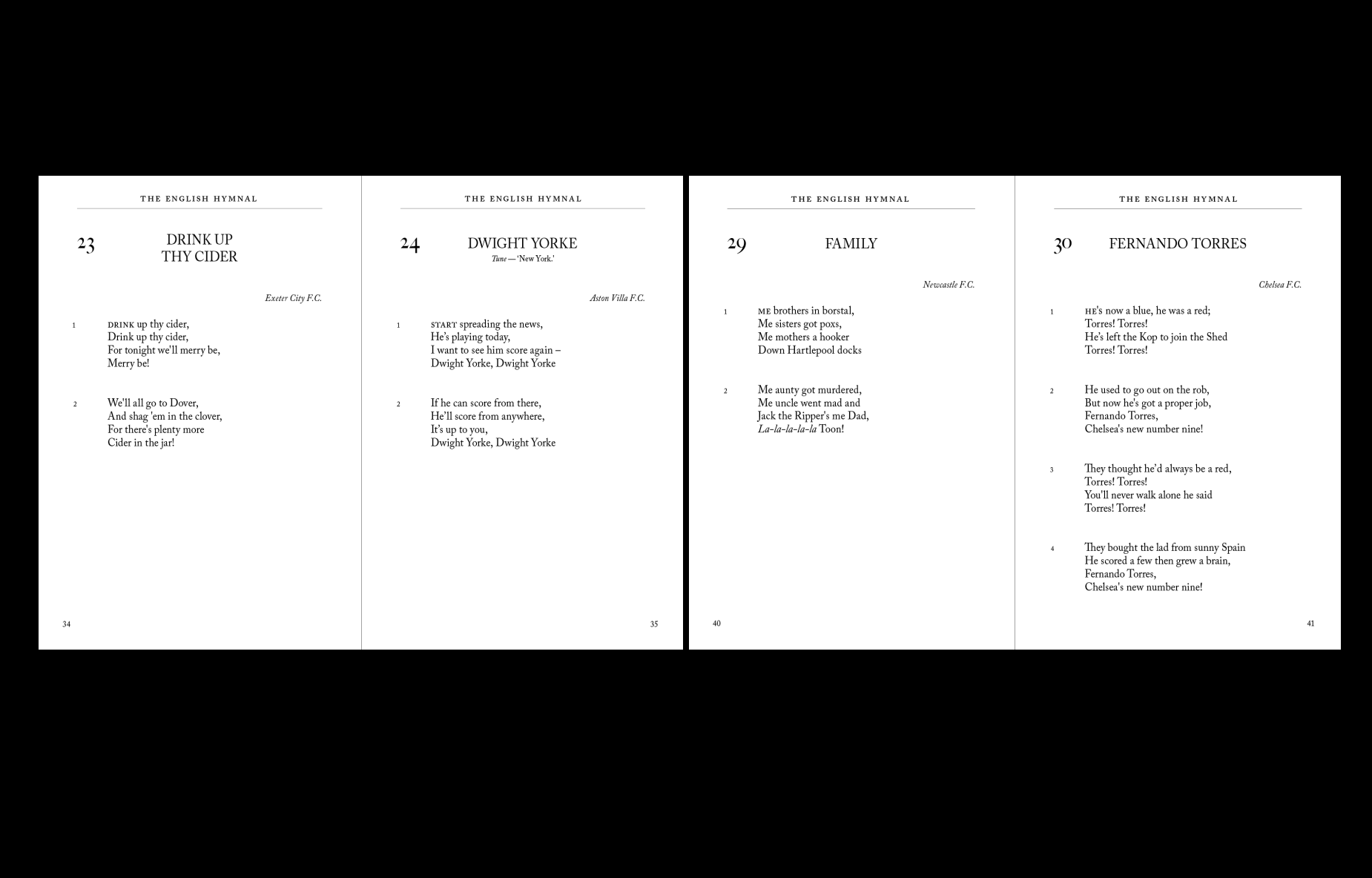

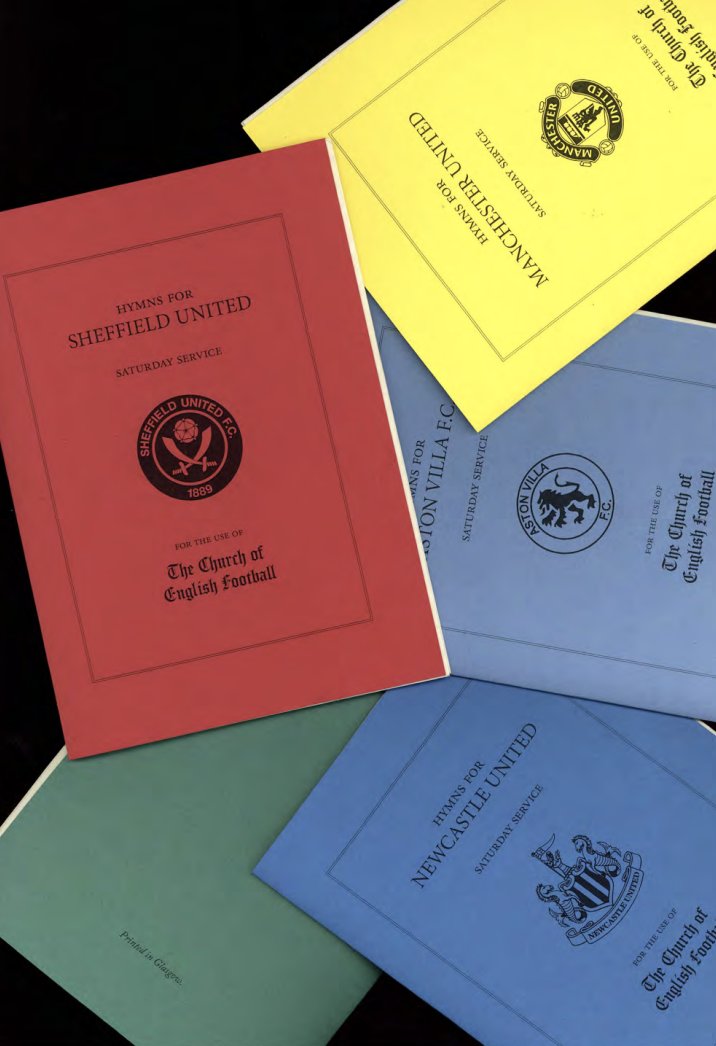

In my research, I found that ‘On the Ball, City’ is supposedly the oldest football song that’s still sung by fans today. It was composed by Albert T Smith who became the director of Norwich City in 1905. ‘Blaydon Races’ was originally a Geordie folk song, before it became an anthem of Newcastle fans. I highly recommend Andrew Lawn’s book ‘We Lose Every Week: A History of Football Chants.’ He makes the point that football chanting could be seen as one of the only remaining forms of oral folk traditions. It was this conclusion that led me to think about about how oral traditions are preserved and archived through tangible means for future generations, so I decided to design the hymn book to preserve this aspect of English cultural heritage, cementing the chants I print.

What’s your favourite football song you found whilst creating the project?

I’m from the south-west, so I’m a fan of ‘Cider! Cider! Cider!’ and ‘Drink up thy Cider’ sung by Exeter City and Bristol Rovers. ‘Who ate all the pies’ is also a classic, and when making my revised ‘Songs of Praise’ episode with the choral singer Lois McColl, was my favourite to hear in her soprano voice. Some of the older chants, such as ‘Rowdy Dowdy Boys’ sung by Sheffield United fans, are really problematic and uncomfy. These chants demonstrate how much progress has been made in terms of inclusivity for women within English football culture.

Find more from Eliza Hart over on her Instagram.